The world’s second-largest economy is at a crossroads. While China’s GDP expanded by 5.4% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2025, matching the previous quarter’s pace, the underlying dynamics tell a more complex story.[1] Behind the headline growth figures lies a economy grappling with structural headwinds, mounting trade policy uncertainty, and a fundamental mismatch between production capacity and global demand. For investors navigating this landscape, understanding these shifts is no longer optional—it’s essential.

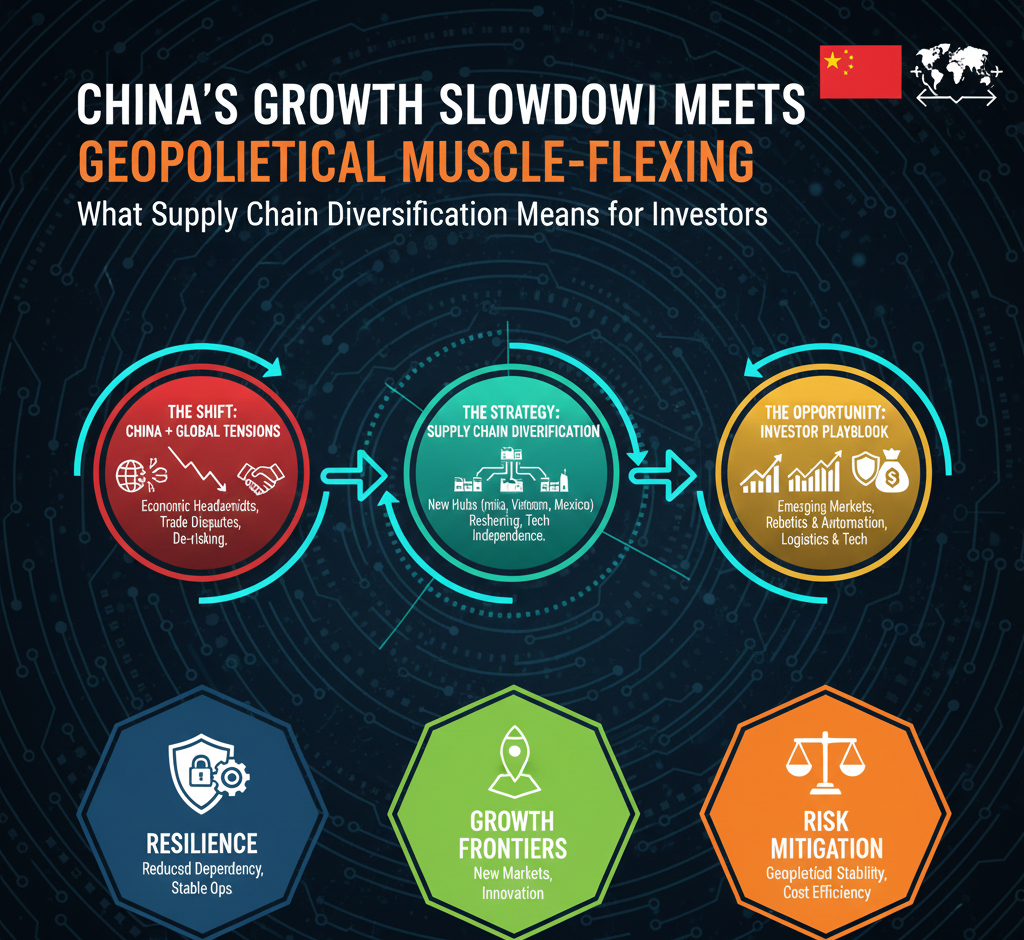

The geopolitical environment has shifted dramatically. Trade tensions, particularly those emanating from Washington, are reshaping how multinational corporations think about their supply chains. Companies that once viewed China as an irreplaceable manufacturing hub are now seriously evaluating alternatives in Southeast Asia, India, and Mexico. This isn’t merely a cyclical adjustment; it represents a structural reconfiguration of global commerce that will reverberate through investment portfolios for years to come.

The Paradox of Growth and Structural Weakness

China’s economic narrative in 2025 presents a paradox worth examining. While the headline GDP growth rate appears solid, the World Bank projects this will moderate to 4.5% in 2025 and further decline to 4.0% in 2026.[1] This deceleration reflects not temporary cyclical weakness, but rather deeper structural challenges that have been building for years.

The property sector, once the engine of Chinese growth, continues to deteriorate. This weakness has cascading effects: construction employment has suffered, investment has contracted, and household wealth has eroded as home prices decline. Between 2020 and 2024, while GDP growth averaged 4.9%, urban employment growth limped along at just 0.9% annually, with only 21 million net new jobs created over five years.[1] This employment-growth disconnect signals that the economy is becoming increasingly capital-intensive while struggling to generate meaningful job creation.

Consumer confidence remains fragile. Retail services sales growth slowed to 5.2% year-on-year in real terms during the first four months of 2025, down from 6.0% in 2024.[1] The culprits are familiar: negative wealth effects from declining home prices, slower income growth compared to pre-pandemic levels, and uncertain employment prospects. Households are saving rather than spending, a rational response to economic uncertainty but one that undermines the consumption-driven growth model that policymakers desperately need.

The Export Illusion and Overcapacity Crisis

Here’s where the geopolitical dimension becomes critical. Chinese exports grew by 6.1% year-on-year in the first seven months of 2025, actually outpacing GDP growth.[2] On the surface, this appears positive. Dig deeper, and a troubling picture emerges: Chinese industrial production has expanded so dramatically that even robust exports cannot absorb the output. The result is mounting overcapacity across manufacturing sectors.

Capacity utilization—a key indicator of how efficiently resources are being deployed—has declined, pointing to a structural imbalance between supply and demand.[2] Producer and export prices have fallen in most months since early 2025, a sign of intense competition and deflationary pressures.[2] This price weakness, while initially appearing beneficial to consumers, actually reflects an economy struggling to find buyers for its expanding industrial base.

The geopolitical dimension amplifies this problem. Trade policy uncertainty, particularly surrounding potential tariffs and protectionist measures from the United States, creates a perverse incentive structure. Chinese manufacturers are rushing to export before tariffs potentially rise, flooding global markets with goods. This temporary surge masks an underlying problem: without genuine demand growth, this export-led strategy is unsustainable.

Stimulus Without Rebalancing: The Policy Dilemma

Beijing’s policy response to these challenges has been substantial but strategically narrow. In March 2025, Chinese leadership announced an increase in the general budget deficit to 4% of GDP, coupled with 1.3 trillion renminbi in ultra-long special treasury bonds and 4.4 trillion renminbi in local special-purpose bonds.[2] The fiscal impulse has shifted from highly negative in mid-2023 to positive in 2025, providing genuine support to growth.[2]

However—and this is crucial for investors—the composition of this stimulus matters enormously. The fiscal expansion has prioritized infrastructure investment rather than consumption support. While infrastructure spending has accelerated, the general budget deficit used to finance routine expenditures including education, healthcare, and public-sector wages has remained largely stable at around 4.85% of GDP.[2]

Consumer subsidies and trade-in programs have received only modest increases. The trade-in program, which encourages consumers to replace old goods with new ones, received 300 billion renminbi in 2025, double the prior year’s allocation, but this remains tiny compared to infrastructure-driven spending.[2] This approach is unlikely to address the fundamental cause of weak consumption: slowing income growth and eroded household wealth.

More concerning for global investors: relaxed monetary conditions have primarily facilitated financing for government spending rather than boosting household or corporate credit.[2] Credit to the public sector has expanded rapidly, while credit to the private sector has declined. This creates a crowding-out risk where government borrowing starves the private sector of capital.

Supply Chain Diversification: The Investor Opportunity

For multinational corporations and investors, these dynamics create both risks and opportunities. The risk is clear: a Chinese economy growing more slowly, with export-dependent manufacturers facing margin pressures from overcapacity and price competition. Companies heavily reliant on Chinese consumption face headwinds for years to come.

The opportunity lies in supply chain diversification. Southeast Asian nations—Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia—are attracting manufacturing investment as companies seek to reduce China concentration risk. India’s manufacturing sector, supported by government incentives, is becoming increasingly competitive. Mexico, benefiting from proximity to North American markets and trade agreements, is emerging as a nearshoring hub.

Investors should consider three strategic implications. First, companies with significant China exposure face pressure on margins and growth. Diversification away from China-dependent supply chains will accelerate. Second, beneficiary nations—particularly those in Southeast Asia and South Asia—will see increased foreign direct investment. Third, the transition period will create volatility as companies manage dual supply chains during the shift.

The Geopolitical Wildcard

Trade policy uncertainty remains the dominant variable. If tariffs on Chinese goods rise substantially, the incentive to diversify supply chains intensifies dramatically. If trade tensions ease, the urgency diminishes. This uncertainty itself is costly, forcing companies to make long-term capital allocation decisions in an environment of genuine ambiguity.

The World Bank’s baseline projection assumes growth moderating to 4.0% by 2026, with fiscal policy partially offsetting external headwinds.[1] However, the International Monetary Fund projects growth of 3.4% by 2030 under its official scenario, while more pessimistic assessments suggest growth could slow to 2.5% if reform efforts falter.[3] This wide range of outcomes reflects genuine uncertainty about China’s policy trajectory and global trade dynamics.

Conclusion: A New Era of Strategic Recalibration

China’s economic slowdown is real, structural, and likely to persist. The government’s policy response—focused on infrastructure rather than consumption rebalancing—suggests policymakers believe the current growth model remains viable. Global investors should not expect a near-term surge in Chinese consumption or a rapid rebalancing toward domestic demand.[2]

Instead, prepare for a prolonged period of slower Chinese growth, continued export pressure, and accelerating supply chain diversification. Companies that successfully navigate this transition—reducing China concentration while building capabilities in alternative markets—will emerge stronger. Investors who recognize these shifts early and position accordingly will find opportunities amid the disruption. The era of China as the default manufacturing hub is ending; the era of strategic supply chain diversification has begun.

References

- https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/8ae5ce818673952a85fee1ee57c3e933-0070012025/original/CEU-June-2025-EN.pdf

- https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/chinese-economy-stimulus-without-rebalancing

- https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/chinas-economic-slowdown-and-spillovers-to-africa/