Anthropology is often described as the science of humanity — a field that studies who we are, where we come from, how we live today, and how we might change in the future. It sits at the intersection of biology, social science, and the humanities, giving us a uniquely holistic view of human life.[1][2]

In a world shaped by globalization, migration, digital technology, and climate change, anthropology offers tools to understand not just cultures far away, but also the institutions, workplaces, and online communities we inhabit every day.

Defining Anthropology

Major reference works define anthropology as the study of human beings across time and space, including their biology, cultures, societies, and languages.[1][2][3]

According to the American Anthropological Association, anthropology explores “what makes us human,” taking a broad approach to everything from genetics and bones to language, rituals, and power structures.[7] Encyclopedia Britannica similarly calls it “the science of humanity,” emphasizing both the evolutionary history of Homo sapiens and the social and cultural features that distinguish humans from other species.[1]

At its core, anthropology asks questions such as:

- How did humans evolve biologically and culturally?

- Why do societies organize family, work, religion, and politics in such different ways?

- How do language and symbols shape what we think is real?

- What can past societies teach us about resilience, inequality, or collapse?

The Holistic Approach: Seeing the Whole Picture

One of anthropology’s defining features is its holistic or integrative approach. Departments and professional associations emphasize that anthropology links the life sciences, social sciences, and humanities to understand humans in context.[5][7]

This means anthropologists rarely look at a single factor in isolation. Instead, they examine how cultural, social, economic, political, environmental, and biological forces intersect to shape human lives.[5] For example:

- A study of food insecurity might combine climate data, crop patterns, local beliefs about food, household income, and global commodity prices.

- Research on migration could consider immigration law, kinship networks, smartphone use, and historical trade routes together.

This integrative view makes anthropology valuable for tackling complex problems like public health, climate adaptation, or social polarization.

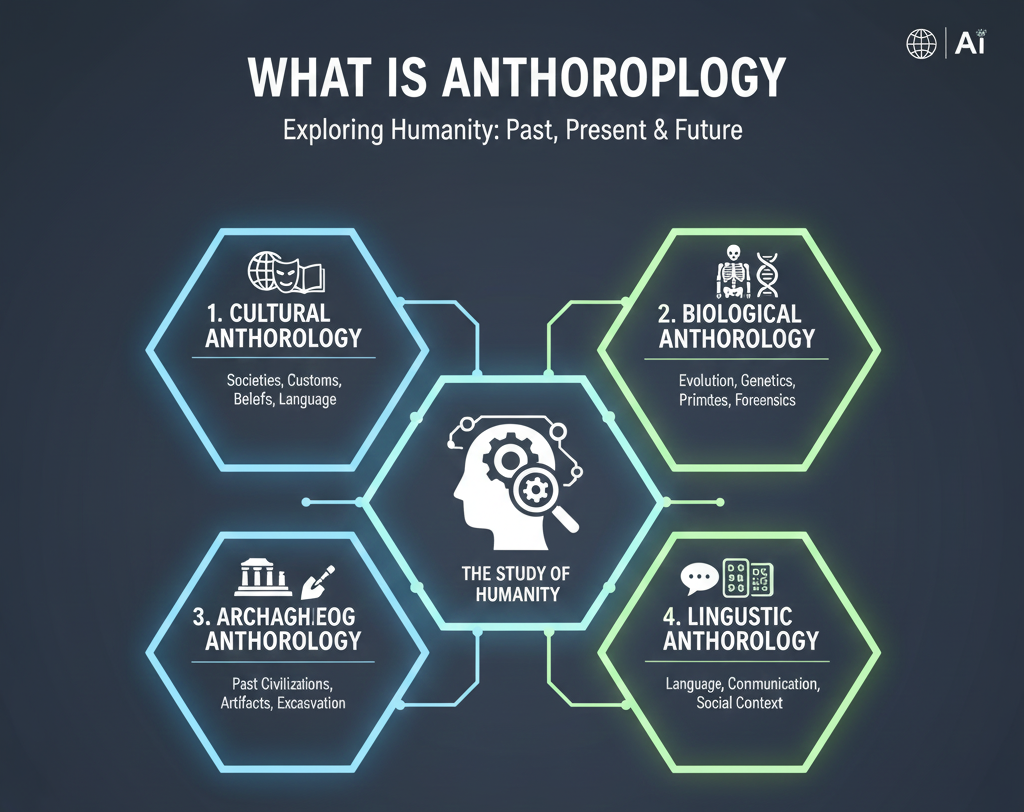

The Four Major Branches of Anthropology

While anthropologists work in many specialties, a widely recognized framework — especially in North America — divides the discipline into four main subfields.[1][2][7]

1. Cultural (or Social) Anthropology

Cultural anthropology (often paired with social anthropology and called sociocultural anthropology) studies how people live, make meaning, and organize social life in different communities.[1][2]

Cultural anthropologists ask questions like:

- How do people in a given society define family, gender, or success?

- What rituals and symbols matter most in political rallies, sports, or religious life?

- How does globalization reshape local identities or traditions?

Using long-term fieldwork, interviews, and participant observation, they might study topics from urban youth culture and climate activism to corporate workplaces or online gaming communities.

2. Archaeology

Archaeology investigates past human societies primarily through their material remains — from stone tools and pottery to monumental architecture and ancient DNA.[1]

Archaeologists analyze artifacts, sites, and landscapes to understand:

- How early farmers organized their settlements and economies

- Why some civilizations expanded and others collapsed

- How trade routes connected distant regions

These findings shed light on long-term patterns in inequality, environmental change, and cultural innovation that continue to shape the modern world.

3. Biological (or Physical) Anthropology

Biological anthropology focuses on the biology and evolution of humans and our closest primate relatives.[1][2]

Key areas include:

- Human evolution and the fossil record of hominins

- Genetic variation among human populations

- Health, disease, and adaptation to different environments

- Primate behavior and cognition

By combining genetics, anatomy, ecology, and field studies of primates, biological anthropologists help explain how human bodies and behaviors evolved — and how they respond to contemporary pressures like urbanization or climate stress.

4. Linguistic Anthropology

Linguistic anthropology examines how language shapes social life — from everyday conversation to law, media, and education.[1][2][7]

Linguistic anthropologists study:

- How different languages categorize time, space, or kinship

- How speech styles signal identity, status, or solidarity

- What happens when languages disappear or are revived

This branch reveals how language is tied to power, belonging, and cultural continuity, and why language loss is often linked to broader struggles over rights and recognition.

Key Methods: How Anthropologists Work

Across these branches, anthropologists use a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. Some of the most distinctive are:

Ethnography and Participant Observation

Ethnography is a hallmark method in cultural anthropology and related fields.[1][7] Researchers spend extended time in a community, learning the language, joining in daily routines, and documenting practices and stories.

Instead of standing apart as detached observers, ethnographers often participate in activities — working in markets, attending ceremonies, or sharing meals — to understand how people themselves make sense of their world.

Interviews, Surveys, and Archives

Anthropologists also conduct structured and unstructured interviews, collect life histories, design surveys, and draw on archival records. This combination helps capture both individual experiences and wider patterns.

Material, Biological, and Digital Analysis

In archaeology and biological anthropology, methods include:

- Excavation, mapping, and spatial analysis of sites

- Laboratory analysis of bones, teeth, seeds, and soils

- Genetic sequencing and isotope analysis to trace diet and migration

Today, anthropologists also study digital environments — from social media platforms to virtual reality — expanding traditional fieldwork into online and hybrid spaces.[2]

Why Anthropology Matters Today

Universities and professional associations emphasize that anthropology’s insights are increasingly relevant to global challenges, from health crises to environmental change.[5][7] Several themes stand out:

Understanding Cultural Difference Without Stereotypes

Anthropology equips us to recognize that practices we take for granted — such as parenting styles, gender roles, or ideas of success — are culturally shaped, not universal. This perspective helps reduce ethnocentrism and supports more nuanced approaches in diplomacy, development, education, and business.[4][5]

Informing Public Policy and Practice

Anthropologists work in public health, urban planning, humanitarian organizations, tech companies, and government agencies. Their research can help:

- Design vaccination campaigns that account for local beliefs and mistrust

- Improve user experience in digital products by understanding real-world practices

- Support community-led responses to climate risks like flooding or drought

Because anthropologists pay attention to lived experience and power dynamics, they often uncover why well-intended policies fail on the ground.

Addressing Inequality and Power

Modern anthropology frequently examines how race, class, gender, and other forms of difference intersect with institutions like law, health care, and policing. By documenting everyday experiences of inequality and resistance, anthropologists contribute evidence and analysis to broader debates on justice and human rights.[2][4]

Anthropology in Education and Careers

Departments describe anthropology as a gateway to careers that require strong analytical, intercultural, and communication skills.[5][6]

Graduates work in:

- International development and NGOs

- Public health and social services

- Museums, heritage, and cultural resource management

- UX research, design, and market research

- Education, journalism, and public policy

The field’s emphasis on qualitative insight, contextual thinking, and ethical engagement is increasingly valued in data-rich but context-poor decision environments.

How to Start Exploring Anthropology

If you want to explore anthropology further, you can:

- Read accessible overviews from major reference sources like Encyclopedia Britannica or university anthropology departments.[1][5][6]

- Browse introductory materials and teaching resources from the American Anthropological Association.[7]

- Look up open-access articles or talks on topics like food systems, migration, or digital cultures from organizations such as National Geographic, which frequently features anthropological perspectives.

Many universities also offer online lectures, podcasts, and short courses that provide a first-hand feel for how anthropologists think and work.

Conclusion

Anthropology is more than the study of “exotic” cultures; it is a systematic, evidence-based exploration of what it means to be human, past and present.[1][2][7] By combining insights from biology, culture, language, and history, it helps us see our own assumptions more clearly and imagine more inclusive futures. Whether you encounter it in a museum exhibit, a UX research report, or an article on climate adaptation, anthropology offers critical tools for navigating an increasingly interconnected yet unequal world.

References

- https://www.britannica.com/science/anthropology

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthropology

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/anthropology

- https://fiveable.me/key-terms/ap-hug/anthropology

- https://anthro.csuci.edu/what-is-anthro.htm

- https://anthropology.ua.edu/about-the-department/what-is-anthropology/

- https://americananthro.org/practice-teach/what-is-anthropology/